This past week was listed on our academic calendar as the Piemonte Stage. The word “stage” is from French and rhymes with “Taj” and not “age.” It refers to an apprenticeship and is most common in the culinary world when a culinary “student” works for free for a chef for a period of time to learn the tricks of the trade. Now its use is spreading and can mean a period of student work experience in any discipline, generally without pay. We will be having four stages in Italy (Piemonte, Puglia, Trentino, and Emilia) and two abroad in France and the UK. Each stage is one week long and we’ve each been assigned one of them to study in depth and to prepare a written and oral report to the class. We all go to all the places together but only a few of the larger group need to pay attention in any one place. Well, we all pay attention, of course, but some of us will be graded on our observations while the rest of us won’t. This past week was sort of a “warm up” stage so none of us had to report on it. We visited several places in Piemonte, our home region. Each day was a day trip by bus to a different venue. I’ve already discussed our visit to Baladin, the institute of snail farming and the cured meat processor. Those visits made up the first two days of our Piemonte stage. After that it was rice, wine, wine, wine and dairy. So, to give you some exposure to the life of a gastronomy student I’ll touch on those visits.

On Wednesday we left Bra at 8:00 AM to travel to the Rondolino rice farm ( http://www.acquerello.it/ENG1.html ). I hadn’t realized that this part of Italy has a lot of rice production and actually supplies 30% of the rice used in Europe. The rice is farmed in the traditional rice paddies using water that comes down from the Alps. Most of the rice grown in Italy is aborio and its most common use in Italy, of course, is risotto.

The farm we visited has been in the family since 1935 and was in the traditional production of aborio rice for the first 25 years. During that time the current owner’s father learned how to grow rice to earn the highest possible earnings. But because rice farming, like much of traditional grain farming, is not a high profit activity (they make about 2% profit) the son, Piero, decided to look around at other possibilities. All rice grown was basically the same product so there was no way to compete there except by growing more. They increased the size of their farm to 600 hectares (~1500 acres). The only way they felt they could grow more would be to move their operation to Nicaragua where one could grow 2 ½ crops per year due to the “eternal summer.” There was also no differentiation in the milling process. All farmers took their rice to a few mills for milling and the resulting rice was all the same.

Piero learned all he could about rice and made some decisions to change the way they produced rice. First, he planted the carnaroli variety of rice instead of the aborio. It is a rice with a higher starch content and firmer texture. It tolerates over cooking better than aborio and doesn’t release its starch into the water as much. It makes it into a “fool proof” rice to cook with. He cut the size of their farm to 140 of the most fertile hectares. He aged the rice after harvest for 1 ½ to 2 years to stabilize the starch. Then he had to deal with milling. Milling takes off the outer coats of the rice grain leaving the white grain that is used in cooking. Milling also takes off the germ where vitamins and other nutrients lie. He decided that he needed to mill his own rice in a gentler fashion so that the grains wouldn’t be damaged (cracked or broken grains release their starch to the cooking water easier) and he wanted to find a way to put the germ back on the granule. He finally found a process to do that by centrifuging the milled rice with the germ that has been separated from the chaff. The process generates heat and the heat “melts” the germ and coats the grain with it. He then decided to pack his rice in cans under a vacuum to preserve it better. The resulting product was branded Acquerello and is considered a “high end” rice brand that is used by many of the world’s top chefs including Alain Ducasse, Heston Blumenthal, and Thomas Keller. They would like to get a wider acceptance of their rice but the public seems scared off by the price and a little by the color and texture of the uncooked rice. It is a little yellower and a bit waxy to the feel due to the germ that is coating the granules. They feel that the ease of cooking this rice (you don’t have to pay so much attention to risotto while it is cooking) and the increased health benefit should sway people but many people (and chefs) feel that rice is rice and the cost is the prime consideration. In their growing of the rice they do not use chemicals.

We had a all rice lunch consisting of a bowl of three varieties of rice so that we could compare them. We could add a bit of rice oil for flavor if we wished. Then they prepared a delicious rice salad accompanied by a rice beer. We had rice cookies and rice ice cream for dessert. They gave us some rice to take home and cook with so we are eager to try it. We were back in Bra at 19:00.

The next day we were to visit two wineries, one in Bra and the other in Castagnole Lanze. It was going to be a tough day. It wasn’t like we would taste just one wine in each winery, no the wineries each made several types of wine and we needed to be exposed to the differences. At least we were provided with some nice cured meat, some cheese, a little bruschetta, some salciccia di Bra, and bread to help clear our palates between glasses. The winery in Bra is the Ascheri winery (http://www.ascherivini.com/welcome_eng.lasso). There we had a couple of Barbera di Alba and Barolo wines. They don’t try to be trendy and do not use too much technology in the production of their wines. Their grapes are selected/sorted in the field, not in the winery. They use Croatian oak, not French, as they think it is milder and better for their wine. They age it 24 months in wood and use only cork in their bottles, which are requirements for Barolos under DOCG regulations.

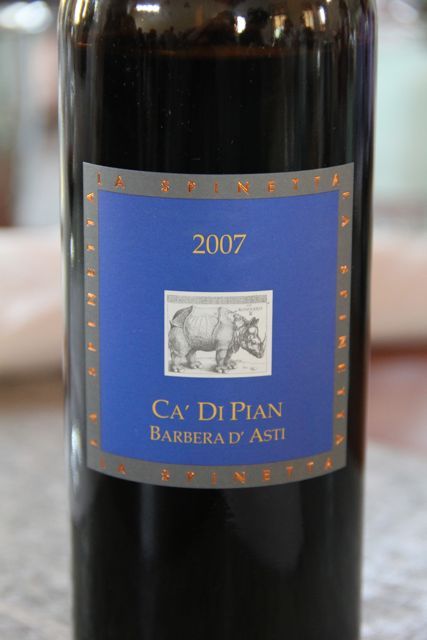

After drinking tasting wine and eating delicious snacks we had lunch and then boarded the bus for Castagnole Lanze to visit La Spinetta winery ( http://www.la-spinetta.com/ ).

La Spinetta started out making Moscatto which is a nice wine to make because it can be sold shortly after making it, not needing aging. They have since purchased two other vineyards, another in Piemonte and one in Tuscany. They have started making Barolo wine fairly recently. They stress quality in the vineyards and do not use chemicals and use green harvest (remove about half the grapes when they are green) so that the remaining grapes get more sugar and the vines develop better with deeper roots. About 80% of their wine is exported with the most going to the United States. We tasted their Barbera d’ Asti, PIN (a blend of barbera and nebbiolo), Barberesco, Barolo and Moscato d’ Asti. The information on the growing and production of these great wines was very interesting.

After the winery visits we went to Pollenzo for a short lecture on photography. We got back to Bra at about 19:40.

On Friday we caught the bus at 7:30 AM to go to the school in Pollenzo where we had some hands on photography instruction while we took pictures around the campus.

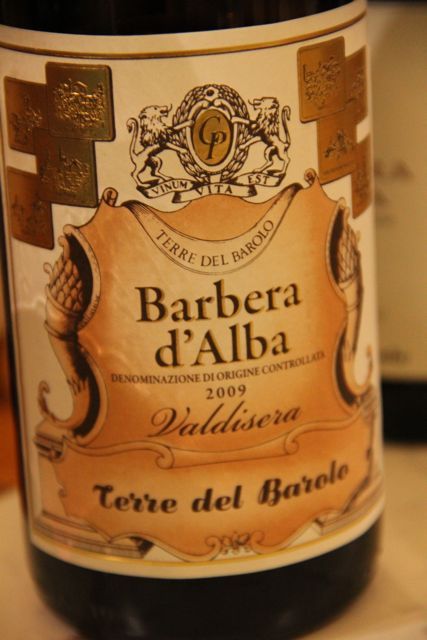

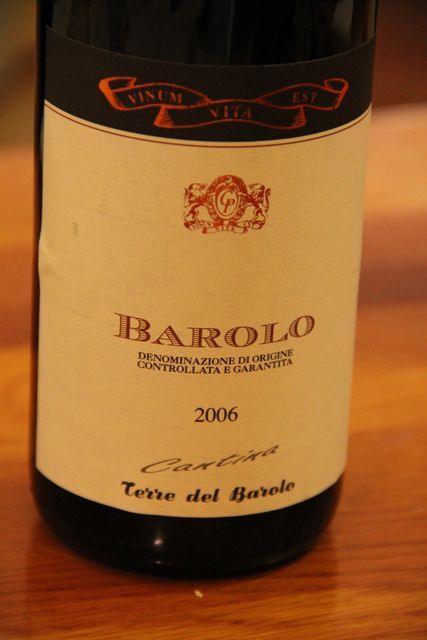

Then boarded our bus for Castiglione Falletto to visit the Terre del Barolo winery ( http://www.terredelbarolo.com/inglese.html ). Terre del Barolo is a cooperative winery with 370 farmer members. Farmers in the cooperative grow the grapes and the wine is made at the winery for all of them. The 30 people who work at the winery have the job of providing the best value to the growers. The wine maker works with the growers to help them produce grapes with the best quality and quantity. They make many different varieties of wine. They are a much bigger operation than the ones we had visited prior to this. Many of their production methods were optimized for speed. During harvest they have to make a lot of wine in a short period of time – 5,500 tons of grapes. They make two types of wine: bottled and un-bottled. The un-bottled is often sold to secondary bottlers. Wines to which they can attach the “names of the vines” (higher quality) is bottled and sold mostly to restaurants. At present growers are paid on the basis of the sugar content of the grapes. Now they are trying to change that to include other parameters of grape quality.

We toured the plant and then we had a nice lunch with wine pairings and were told more about the wines we tasted.

We then traveled to San Vittore di Fossano to visit the Cagnassi farm. This is a dairy farm that is starting to get into the production of some dairy products such as yogurt and cheese. They are pretty early into those endeavors, however. We learned about how they ran their dairy farm including the breeding and raising of cows. We go to do a little hands-on cheese making, but we had seen the same thing done at school.

We returned to the school in Pollenzo where Josh Viertel, president of Slow Food USA talked with our class. He is a dynamic fellow and discussed with us the direction they are trying to take Slow Food USA and why they have chosen those goals. We were all tired after our long day but none of us wanted him to stop. Since we are a small group the talk was more of a dialog than a presentation. The school people had to put an end to the meeting as the bus driver needed to get home. They are going to try to schedule another session Monday afternoon after class with him if his schedule permits. Many in the class were very excited by what he was saying and for many the issues he discussed are why we are here. We returned to Bra about 20:00. It was a very long day at the end of a very long stage, but it was all very educational and stimulating. The wine was good too.

Ciao!

Wonderful!<o:p></o:p>From: Over The Table [mailto:post=overthetable.posterous.com@posterous.com] On Behalf Of Over The TableSent: Sunday, April 17, 2011 3:44 PMTo: mclaire4@comcast.netSubject: [overthetable] Piemonte Stage<o:p></o:p>